City governments play an integral role in helping citizens through extreme heat and wildfire smoke. By leveraging communication and creating comprehensive, realistic plans, the city can work with organizations to ensure citizens are well-equipped to deal with extreme weather events. There are numerous frameworks that cities have used to plan for extreme weather events.

In general, city plans should:

Be made before fire season starts (usually July-October in WA state).

Take into special consideration those who are part of critical populations and those more likely to experience negative health effects due to wildfire smoke and extreme heat, including:

Non-English speakers

Local leadership

Media

Older adults

Outdoor workers

Unhoused people

People with mental/physical illnesses/disabilities

People without health insurance

People with pre-existing medical conditions (especially heart and lung conditions)

Pregnant people

Tourists/recreators

Youth

People 65 or older or younger than 18

Those with no access to AC or closed loop AC

Consider the organizations that serve vulnerable populations.

Be understandable and relevant, using language and visuals that do not require previous education or knowledge for full comprehension.

Have specific actions that are taken during a smoke event to ensure that continuously updated air quality data is reaching citizens.

AirNow.gov and NowCast are great options and are publicly accessible.

Continuously encourage citizens to be prepared for a smoke or heat event by using local media, community organizations, or other public agencies.

Alter communication strategies based on geography and demographics.

Include information on how to shelter in place, the risks of long-term smoke exposure, and how to know when relocation is necessary.

Determine clear activation thresholds for extreme weather such as heat, smoke, and cold. Once these thresholds are met, specific actions are taken by organizations and the city to ensure communication and resources are dispersed widely.

Wildfire smoke is not good for anyone’s health, but there are ways to reduce exposure to it.

Certain populations are more vulnerable to the adverse effects of wildfire smoke.

|

At-risk Lifestage/Population |

Rationale and Potential Health Effects from Wildfire Smoke Exposure |

|---|---|

| People with asthma and other respiratory diseases |

Rationale: Underlying respiratory diseases result in compromised health status that can result in the triggering of severe respiratory responses by environmental irritants, such as wildfire smoke. Potential health effects: Breathing difficulties (e.g., coughing, wheezing, and chest tightness) and exacerbations of chronic lung diseases (e.g., asthma and COPD), leading to increased medication usage, emergency department visits, and hospital admissions. |

| People with cardiovascular disease |

Rationale: Underlying circulatory diseases result in compromised health status that can result in the triggering of severe cardiovascular events by environmental irritants, such as wildfire smoke. Potential health effects: Triggering of ischemic events, such as angina pectoris, heart attacks, and stroke; worsening of heart failure; or abnormal heart rhythms could lead to emergency department visits, hospital admissions, and even death. |

| Children (< 18 years of age) |

Rationale: Children’s lungs are still developing, and there is a greater likelihood of increased exposure to wildfire smoke resulting from more time spent outdoors, engagement in more vigorous activity, and inhalation of more air per pound of body weight compared to adults. Potential health effects: Coughing, wheezing, difficulty breathing, chest tightness, decreased lung function in all children. In children with asthma, worsening of asthma symptoms or heightened risk of asthma attacks may occur. |

|

Pregnant people |

Rationale: Pregnancy-related physiologic changes (e.g., increased breathing rates) may increase vulnerability to environmental exposures, such as wildfire smoke. In addition, during critical development periods, the fetus may experience increased vulnerability to these exposures. Potential health effects: Limited evidence shows air pollution-related effects on pregnant women and the developing fetus, including low birth weight and preterm birth. |

| Older adults |

Rationale: Higher prevalence of pre-existing lung and heart disease and decline of physiologic process, such as defense mechanisms. Potential health effects: Exacerbation of heart and lung diseases can lead to emergency department visits, hospital admissions, and even death. |

| People of low socio-economic status |

Rationale: Less access to health care, could lead to higher likelihood of untreated or insufficient treatment of underlying health conditions (e.g., asthma, diabetes), and greater exposure to wildfire smoke resulting from less access to measures to reduce exposure (e.g., air conditioning). Potential health effects: Greater exposure to wildfire smoke resulting from less access to measures to reduce exposure, along with higher likelihood of untreated or insufficiently treated health conditions could lead to increased risks of experiencing the health effects described above. |

| Outdoor workers |

Rationale: Extended periods of time exposed to high concentrations of wildfire smoke. Potential health effects: Greater exposure to wildfire smoke can lead to increased risks of experiencing the range of health effects described above. |

Table 1. Summary table of life stages and populations potentially at greater risk of health effects due to wildfire smoke exposures from an EPA webpage 1. The at-risk populations include people with asthma and other respiratory diseases, people with cardiovascular disease, children, pregnant people, older adults, people of low socioeconomic status, and outdoor workers.

In the King County Wildfire Smoke Response Plan, actions the Public Health department can take to ensure citizen health and safety are described. This framework focuses on preventative action and provides many specific strategies to meet each objective which can help other cities design their own plan.

King County Wildfire Smoke Response Plan Updated June 2024

Visit this research report if you are curious about:

This 2024-2029 Western Montana plan describes ways this region is reducing or eliminating long-term risk to people and property from disasters or hazardous events.

WESTERN MONTANA - Regional Hazard Mitigation Plan

Visit this wildfire smoke preparedness plan to learn about how Garfield County is building smoke-ready communities:

2022 Garfield County - Community Wildfire Protection Plan

Visit this 2023 Klamath County Public Health smoke response plan to learn about specific actions this county is taking to enhance smoke response on a city scale:

Visit this link to see Seattle and King County’s extreme heat response plan:

Public Health – Seattle & King County - Extreme Heat Response Plan

Visit this link to see how Boston is better preparing for and mitigating extreme heat:

Heat Resilience Solutions for Boston

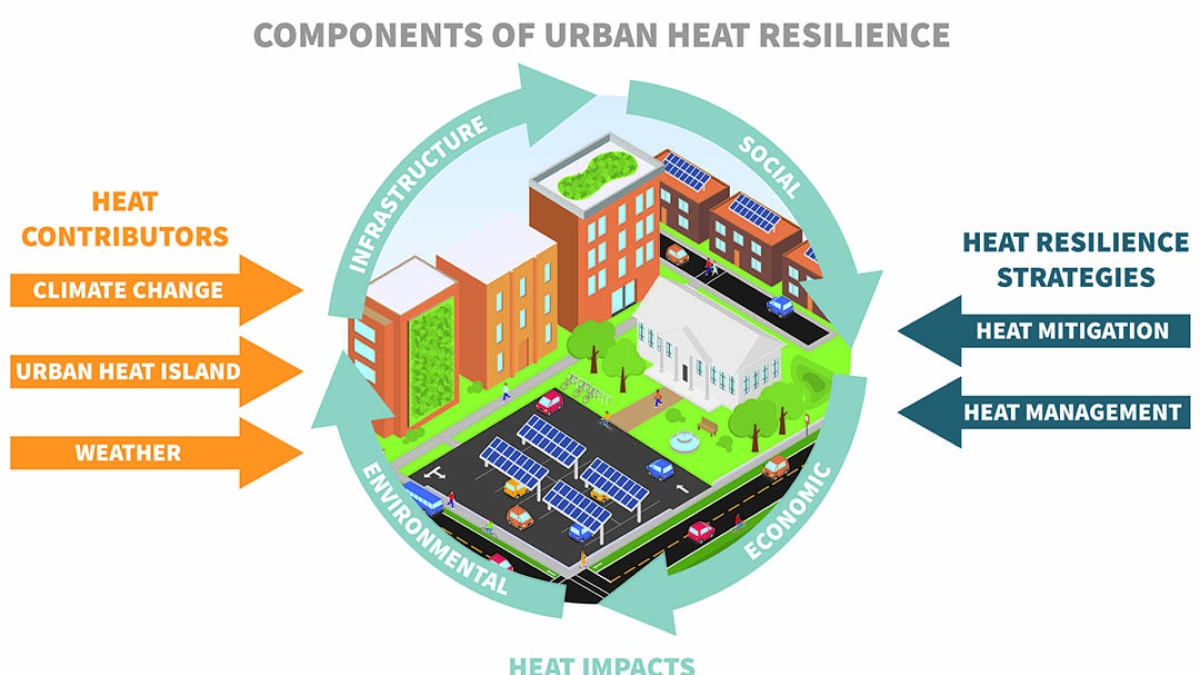

Figure 1. Graphic depicting components of urban heat resilience 2.

As a city develops plans around extreme heat and smoke safety, it is important to consider whether significant urban heat islands are present and what communities they affect. Here in Spokane, Gonzaga University’s Climate Institute studied the urban heat island effect and how it is exacerbated by climate change. To learn more about this project visit:

To learn more about the urban heat island effect on a national level and community efforts to reduce this occurrence, visit:

Figure 2. Graphic depicting the urban heat island effect 3.

Cities can ensure educational materials and resources for heat and smoke safety are accessible to each unique community through Resilience Hubs. This concept was developed by Communities Responding to Extreme Weather (CREW) and the Urban Sustainability Directors Network (USDN). Equipped with green infrastructure, citizens can visit these hubs during extreme weather events and in everyday life. Optimally these hubs build resilience by providing a space for communities to come together and grow. It is vital for a city or organization to strategically choose locations of hubs so that they are accessible to all demographics. To learn about how Spokane is implementing Resilience Hubs, visit:

Resilience Hubs | Gonzaga University

To learn more about Resilience Hubs and their core components, visit:

Resilience Hubs - USDN: Urban Sustainability Directors Network

Communities Responding to Extreme Weather (CREW)

On the USDN site you can also find progress reports of resilience hub networks nationwide under the core components tab, as well as the Resilience Hub YouTube series under the resources tab.

Figure 3. Example of an urban rowhome/building converted to a resilience hub 4.

For a comprehensive smoke-ready toolbox and more research, visit:

This resource is a tool for local governments and provides a suggested community heat action checklist:

Visit this research article in the Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning to learn about urban heat governance in five large, climatically-diverse U.S. cities. The researchers evaluated these cities’ comprehensive, climate action, and hazard mitigation plans so that policymakers can best engage in heat mitigation and management.

Americares is a global non-profit health organization focused on helping uninsured, underinsured, and low-income individuals. Their website on Climate Resilient Health Clinics provides downloadable tools for health providers, patients, and administrators to minimize the impacts of extreme heat and wildfire smoke on human health. Public health should be a top priority for cities, and this resource can aid in information dissemination.

United States Environmental Protection Agency, “Which Populations Experience Greater Risks of Adverse Health Effects Resulting from Wildfire Smoke Exposure?,” September 2019. https://19january2021snapshot.epa.gov/wildfire-smoke-course/which-populations-experience-greater-risks-adverse-health-effects-resulting_.html.