Catholic missionaries in the Northwest Territories continued the Judeo-Christian tradition of translating the Bible into the language of the people, so that they could hear the scriptures in their own speech. Thus the missionary-priest from Sicily who was to found Gonzaga University, Joseph Mary Cataldo, S.J. (1837-1928) quite naturally translated the Gospels into Nez Perce. He and his fellow Jesuits also produced other biblical translations into native languages, as well as catechetical and liturgical materials and hymns. Notably the printed Nez Perce grammar of 1889 credits tribal people with intellectual collaboration in this work. This two-part exhibition presents a sampling of this evangelical translation work and also shows the historical tradition of such translation, from the Septuagint through the Nez Perce translations.

Materials from The Archives of the Oregon Province of the Society of Jesus remain securely in the vault during this exhibition: High-quality color photocopies are on display, displayed by permission of the Archives. While this exhibition focuses on Nez Perce translations, a variety of languages were used by the missionaries, so that Jesuit biblical translations, hymns, and catechesis can be found in Crow, Blackfoot, Assiniboine, etc. Invaluable resources for the research for this exhibition were The Northwest Digital Archives and the Guide to the Microfilm Edition of the Oregon Province Archives of the Society of Jesus Indian Language Collection: The Pacific Northwest Tribes, by Eleanor Carriker, Robert C. Carriker, Clifford A. Carroll, S.J., and W. L. Larsen (Spokane: Gonzaga University, 1976).

The Judeo-Christian tradition is that learning is in service of the faith. As Pope Benedict XVI reaffirmed on April 17, 2008, Education is integral to the mission of the Church to proclaim the Good News.1 The general purpose of education is to help one to be a better person, while missionaries and priests also use their education to help them teach the faith and help the faithful to live it fully. This is why Jesuit missionaries to the Pacific Northwest often brought with them books in theology and philosophy, as shown in the exhibition Treasures from the Vault. Because of their knowledge of Latin and Greek, these priests were able to learn from the people they encountered the native languages of those peoples. As a result, the missionaries could translate Christian materials into those languages, and the Gospels were among the first texts translated.

In order to give the people as full a presentation as possible of the Gospels, Father Cataldo prepared two translations. The one shown here is a synthesis of the four Gospels put into one continuous narrative.

Jesus-Christ-nim kinne uetas-pa kut ka-kala time-nin i-ues pilep-eza-pa taz-pa tamtai-pa numipu-timt-ki.The Life of Jesus Christ from the Four Gospels in the Nez Perces Language, translated by Joseph M. Cataldo, S.J. (1914) [Portland, Ore.: Press of Schwab Printing Co., c. 1915]. (SPEC COLL PM2019.Z7 1914). In the top line of the title, the particle -nim indicates the possessive, as seen in Haruo Aoki's Nez Perce Dictionary, also on display from November 5 onwards, thanks to a gracious loan of that volume from the Nez Perce Tribe. To protect the rare books from excessive exposure to light, the opening on display will be changed each month. October: the front cover; November: pp. 225-226, the Sunday after Pentecost; December: pages 12-13, Christmas.

Shown here is the Gospel reading for Christmas. It is of great cultural value to know that the Jesuit priests were proclaiming the  Gospel to the people in their own language during the eucharistic mass.

Gospel to the people in their own language during the eucharistic mass.

Father Cataldo also translated the four Gospels individually. The readings for Ash Wednesday (from Matthew) and for Easter Monday through Pentecost (from Luke) will be on display in the Cowles Rare Books Library, in high-quality color photocopy. Gospels in Nez Perce, undated. Jesuit Oregon Province Archives, Indian Languages: Nez Perce Collection IL-20 (6, D12).

|

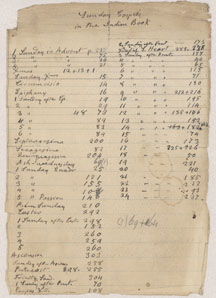

The simple slip of paper shown at left is additional, valuable evidence that Father Cataldo and other priests were proclaiming the Gospels in the language of the people during the mass. Father Cataldo hand-wrote this list of all the Sunday lections, indicating for each the pages where the reading can be found in the book shown above. Also on the list are the major feasts such as Christmas, which sometimes fall on a weekday. For a transcription of this list, click here. "Sunday Gospels in the Indian Book." Jesuit Oregon Province Archives, Joseph Cataldo, S.J., Personal papers:18. Image reproduced here by permission of the Archives. |

On another slip of paper Father Cataldo wrote out the Seven Words of Christ on the Cross. He included the Nez Perce translation for Jesus' words to His mother and to St. John at the foot of the Cross (John 19:26-27).2

Also in the archives is a straightforward Sunday Lectionary in Nez Perce, further evidence that the Gospels were being proclaimed in the language of the people during the eucharistic mass.

"Gospels for Every Sunday of the Year in the Numipu Language or Nez Perces for the use of the St. Joseph's Mission, S.J., in Oregon and Idaho." Books 1-7. [By Joseph Lajoie, S.J., undated.] On display will be copies of the archival title card and the reading for the First Sunday of Advent. Jesuit Oregon Province Archives, Indian Languages: Nez Perce Collection, IL-20 (37).

The Lord' s Prayer and other prayers useful to the people were also put into the native languages. Shown here in the middle of the right hand page is the Lord' s Prayer in Nez Perce. Where new Christian terms occur in the prayer, Father Cataldo added footnotes using Nez Perce language to explain those terms. In this way he insured that the priests could explain Christian concepts to the people in their own language.

Prayers, Catechism, Hymns in the Nunipu Language (Nez Perce) for the use of the St. Joseph' s Missions, S.J., in Oregon and Idaho, trans. Joseph M. Cataldo, S.J. Pendleton, Oregon: Pendleton Printery, J. Huston, 1909 (SPEC COLL E99.N5 C37 1909)

Also on display in Cowles, though not shown here, are a prayer card printed in Nez Perce and several slips of paper on which Fr. Cataldo jotted notes on language, including indications that he was translating parts of the Psalms and Epistles and Apocalypse into Nez Perce. On one slip, he wrote the phrase "All good things" and then gave three possible ways of expressing this in Numipu. It is possible he was working out the Nez Perce for the passage in the Epistle of James in which the disciple wrote that "All good gifts and all perfect gifts come down from above, from the Father of Lights" (James 1:17). One phrase he works on translates "unspeakable joy."3

Handwritten in a small notebook are several Christian prayers in Nez Perce, and beneath each line is added a literal English translation of the Nez Perce. Nez Perce is here presented as the essential and normative text, because that was the version important for the people to understand. The role of English in this notebook is merely an aid to the missionary-priest, who needed to be able to understand the Nez Perce version in order to explain it effectively to the faithful. On display will be the front cover and the opening on which the Creed begins. "Prayers in Nez Perce language and translation." [trans. Edward M. Griva, S.J.] Undated. Jesuit Oregon Province Archives, Indian Languages: Nez Perce Collection, IL-20 (36, D11).

On October 23, 2008, Ann McCormack-Adams, Cultural Arts Coordinator of the Nez Perce Tribe, graciously lent Gonzaga University a copy of the Nez Perce Dictionary by Haruo Aoki, so that it might be included in this exhibition. This gracious and active collaboration is greatly appreciated, and the dictionary has now been added to the second display case in the Cowles Rare Books Library. The Dictionary is also on order for the Jesuit Oregon Province Archives, so it will have its own copy. A different linguistic book prepared by Jesuits and Indian collaborators in 1888 (see below) was removed from display to make room for the dictionary, but remains in this online exhibition.

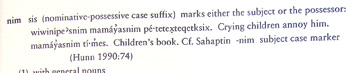

Haruo Aoki, Nez Perce Dictionary. Berkeley / Los Angeles / London: University of California Press, 1994. On loan from the Nez Perce Tribe. Gonzaga University owns three other linguistic works on Nez Perce by this author. The volume on display has, on both front and back endpapers, the round embossed stamp of the Tribe, reading NEZ PERCE TRIBE / TREATY OF 1855. November: an opening showing line drawings to illustrate the words. December: p. 487, including the definition of the particle nim, as seen in the title of Fr. Cataldo's book, above.

At right is the beginning of Professor Aoki's detailed entry on nim, showing that it  indicates possession. Thus, Jesus-Christ-nim (the beginning of the title of Fr. Cataldo's book on the life of Jesus Christ) means "of Jesus Christ."

indicates possession. Thus, Jesus-Christ-nim (the beginning of the title of Fr. Cataldo's book on the life of Jesus Christ) means "of Jesus Christ."

The missionaries also prepared a range of language materials so that the priests could learn the people' s native speech in order to  converse with them and to translate biblical and liturgical texts. Significantly, the priests who published the grammar credit the tribal people they were serving with assisting in the preparation of the volume. This shows respect for the Nez Perce's expertise in their own language. Shown here is the beginning of the verb to think (Latin: cogito) in Nez Perce. The full presentation of this verb with all its tenses and inflections runs several pages. The title page refers to Nunipu as the language common (Latin: vulgo) to the Nez Perce people, using the same Latin word which gives us the name Vulgate for the Latin Bible.

converse with them and to translate biblical and liturgical texts. Significantly, the priests who published the grammar credit the tribal people they were serving with assisting in the preparation of the volume. This shows respect for the Nez Perce's expertise in their own language. Shown here is the beginning of the verb to think (Latin: cogito) in Nez Perce. The full presentation of this verb with all its tenses and inflections runs several pages. The title page refers to Nunipu as the language common (Latin: vulgo) to the Nez Perce people, using the same Latin word which gives us the name Vulgate for the Latin Bible.

Paradigmi verbi activi lingua numpu [!] vulgo Nez-perce, studio Pp. missionoriorum [!] S.J. in Montibus Saxis pro eorumdem privato uso. by Anthony Morvillo and Joseph Cataldo. Desmet, I[daho] T[erritory]: Typis Missionis SS. Cordis, Indis convictis collaborantibus[with the collaboration of Indians who had become convinced (of the truth of Christianity)], 1888. On display in October only, then removed to make space for displaying Haruo Aoki's Nez Perce Dictionary.(SPEC COLL PM2019.M6 1888)

Fr. Cataldo in effect recycled numerous slips of paper and envelopes, recording on them his notes on native languages as he learned them. These show his interest in the people and their language and his respectful care to learn their culture and how they expressed their thought. Some of his lists of toponyms and languages will be shown in the actual exhibition.4

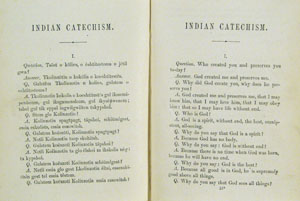

In the late nineteenth century, this volume prepared for the Young People' s Library series shows that Catholics thought adolescents across the country would benefit from learning the history and encountering the language of Native Americans. Shown here is the start of the Catechism in Kootenai.

Pierre Jean de Smet,S.J. "Indian Catechism." Included in his Indian Sketches. New York: D.J. Sadlier, 18--? (SPEC COLL E77.S64 1800z)

Universally religious song is important in worship. Printed books produced by the missionaries record the texts of hymns in Nez Perce and in other tribal languages. An example is the 1909 volume of Prayers, Catechism, Hymns in the Nunipu Language displayed above. The hymns in that volume have Latin or English titles and texts in Nez Perce. Several of these hymns are clearly translations of traditional Latin hymns, such as "Veni Creator" (on pp. 38-39). Other hymns in that volume include "Mary," "Confidence" and "Long Live the Pope" (pp. 44, 45, 48).5

Musically and culturally a handwritten hymnal in the Archives is valuable. It presents full musical settings handwritten on pre-scored paper. Most hymns have a vocalist line and a staff of 3-6 part harmonization. Two hymns appear to be set for a three-voice choir and one appears to be set for a four-voice choir. Some hymns appear to be translations of traditional Latin hymns, such as the Nez Perce version of "Angels We Have Heard on High" (immediately recognizable from its refrain of Glo-o-o-oria...). But others appear to be original compositions, quite possibly based on native chant.This would be exciting regional evidence of the same tradition one sees in Slavic Christianity, where the Greek missionaries translated the liturgy and texts into Slavonic, and the chant used at liturgy was a new, Slavonic chant.

All hymns in the handwritten hymnal are in Nez Perce. Although a few have their title in Latin or English, such as "Veni, Creator" and "Stabat Mater" and "Jesus, Mary, Joseph," most have titles as well as texts in Nez Perce. Sometimes the title is followed by a parenthetical English note identifying the occasion or focus of the hymns, such as "Sacred Heart" or "Christmas."

Hymn no. 5, "Jesus zalaui hi timipnisa." From Indian Hymn Book. Unknown author. Dated 1909, at St. Joseph' s Mission, Slickpoo, Idaho. Jesuit Oregon Province Archives, Indian Languages: Nez Perce Collection, IL-20 (29, D11)

When Europeans realized that another entire hemisphere existed, the Lord' s commandment to teach all nations was discovered to have broader meaning. The new translation work that arose in the Western Hemisphere continued the practice long in place in the rest of the world. The Council of Trent in the sixteenth century simply affirmed the long-recognized obligation of bishops and parish priests to preach in the vernacular.6 This had already been the practice for centuries. Bishops in synod in medieval France, for instance, had directed parish priests to be sure to translate the Gospels and the Creed into French, so that the faithful could understand. And King Alfred in Anglo-Saxon England urged that true pastoral care involved translating the Gospel readings and the Creed for the people. These translations supplemented the Latin of the mass. In Eastern Europe when the Greek monks SS. Cyril and Methodius brought the Gospel to the Slavs, there had been no written language. The missionaries devised an alphabet that had all the native sounds--called the Cyrillic alphabet after S. Cyril-- and then began translating religious materials, starting with the Gospels, the Psalms, and the liturgy. The hymn texts were translated from the ancient Greek hymns of the early Christians, and new Slavonic chant was developed. In the fifteenth century the archbishop of Granada encouraged priests to begin the homily by translating the biblical readings into the vernacular (perhaps Arabic as well as Spanish).7

Thus it was a natural move for vernacular translation to be widespread in the New World also. The Bible and catechism and other basic Christian texts were put into the diverse languages of the peoples of Central and South America.

CENTRAL AMERICA. Because pictorial symbolism was basic to communication in Mexico, Fr. Jacobo de Testera, a Franciscan who arrived there in 1529, developed a pictorial system to teach Christian doctrine. Because artwork relying on feathers was culturally important in this region, new creations such as icons depicted in feathers were made.

On display in Cowles: Jaime Lara, Christian Texts for Aztecs: Art and Liturgy in Colonial Mexico (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1998). On loan from Dr. Catherine Brown Tkacz. October: p. 50, Testerian catechism attributed to Bernardino de Sahagun, early seventeenth century. November: p. 57, The Acts of the Apostles (the conversion of Saint Paul) in Nahuatl. December: p. 133, feather icon of Christ the Savior of the World, sixteenth century.

The baptizing and blending of cultures is shown in a manuscript illustration on the front dust jacket of Lara's book, also on display in Cowles: Codex Tlatelolco, almanac, panel for year 1565. The miniature shows the seated ruler of Tlatelolco wearing the blue Aztec miter. Behind him is a eucharistic tabernacle crowned by green feathers. Madrid, Biblioteca Nacional de Anthropologia e Historia, MS 35-39.

SOUTH AMERICA. Juan Rojo Mejia y Ocon began as a parish priest in Lima, Peru, and then held the chair of Quechua at the university of San Marcos. He focused on teaching parish priests how to translate the Gospel readings into Quechua, the main native language group, still spoken today by eight-to-ten million persons in Bolivia, Ecuador and Peru. Likewise, paraphrases of the Gospels in Quechua can be found in the sermonarios, collections of liturgical sermons produced to assist parish preachers. The Third Lima Council (1585) created an official corpus of catechetical texts in languages including Mochica, Puquina, and Guarani and some varieties of Quechua and Aymara.8

Vitally important was the theological and philosophical argument against slavery. St. Paul had condemned the sin of slavetrading (1 Tim. 1:10) and church fathers including St. Thomas Aquinas had likewise explained that it was sinful. The case against slavery was articulated most fully after the discovery of the New World. While some people wanted to exploit the newly encountered peoples, even to enslave them, others justly argued against this and affirmed and set forth the case against this. In 1462, Pius II denounced slavery as a great crime (magnum scelus); in 1537 Pope Paul III forbade the enslavement of the Indians.9 The philosophical argument against slavery worked out by Jesuits and Dominicans in Spain was particularly important in supporting the attempts by the Church to forbid, and where they could not accomplish that, to limit slavery. Cajetan (1480-1547), a Dominican, did foundational work, and the Jesuit Francisco Suarez (1548-1617) developed the theory of inalienable human rights. Francisco de Vitoria, professor of theology at the University of Salamanca, denounced Pizarro' s conquest of Peru (1531-33) as invasion and affirmed, "Every Indian is a man, and is thus capable of attaining salvation or damnation. ... By natural law, all men are born equal. Legal slavery is the product of the law of nations and thus can be abolished.... The Indians have the right not to be baptized and not to convert to Christianity. ... The Indian peoples are sovereign republics...." Diego de Covarrubias (1512-77) echoed the thought of de Vitoria in 1547. The Gonzaga Collection holds early editions of Cajetan, Covarrubias and others.

On display at Cowles: Francisco de Vitoria, Derechos y deberes entre Indios y Espanoles en el Nuevo Mundo [The Rights and Obligations of Indians and Spaniards in the New World], text reconstructed by Luciano Perena Vicente. (Salamanca: Universidad Pontificia de Salamanca, The Catholic University of America [Washington], Comision Nacional Quinto Centenario [Madrid],1991). On loan from Dr. Michael W. Tkacz. Quotations from pp. 17, 19, 23.

The roots of the translation of Christian religious texts into diverse languages are first Jewish and then Pentecost. The original liturgical language for the Jews was, of course, Hebrew. The Torah and Psalms were written in it, and the Jewish people spoke that language. During the time of the Babylonian Captivity, however, many Jews became less familiar with Hebrew as they learned the language of those who had conquered them. Aramaic, a dialect of Hebrew, became widespread, and the language of the culture was Greek. Jewish leaders therefore had the Torah (the first five books of the Old Testament) translated into Greek, and by the second century before Christ, the entire Hebrew Bible was translated into Greek. At Synagogue services there were double readings. That is, the rabbi would first read the scriptures in Hebrew and then read them a second time in Greek, so that everyone would be able to understand it.

The Greek-speaking Jews who had translated the Hebrew Bible chose, out of reverence, to retain certain Hebrew words, simply putting their sounds into Greek. Later St. Jerome and other Christian translators of the Bible followed this Jewish tradition and kept the same words in Hebrew. These words include Alleluia, Amen, cherub, and seraph. In Father Cataldo' s translation of the Lord' s Prayer, for instance, he concluded with Amen.10

Written in 1008, the Leningrad Codex is the oldest complete manuscript of the Hebrew Bible in what is known as the Tiberian mesorah. The Aleppo Codex is older (c. 930), but since 1947 parts have been missing from it.

The Leningrad Codex: A Facsimile Edition. Ed.David Noel Freedman et al. (Grand Rapids, Mich.: William B. Eerdmans; Leiden / New York: Brill Academic Publishers, 1998) (SPEC COLL BS715.5 L46 1998). October: pp. 14-15, the start of Genesis; November: pp. 74-75, the start of Exodus; December: pp. 456-57, Isaiah 7:6ff, the prophecy of the virgin birth. The original is in the Russian National Library, Firkovich B 19 A.

The oldest manuscripts of the Greek Bible have been reproduced in valuable facsimile editions, and The Gonzaga Collection contains them all: The Codex Vaticanus (before 330?), Codex Sinaiticus (330-350), and the Codex Alexandrinus (5th century), the latter in two editions. These all include the Jewish translation of the Old Testament into Greek (called the Septuagint or Old Greek). The facsimile edition on display is of particular interest because it was made before photography was invented: Charles Woide, a Polish assistant librarian at the British Museum, ingeniously designed individual type pieces that would allow reproducing the famous manuscript. Joseph Jackson then created the individual type pieces. Only 485 copies of this volume were printed.

Novum Testamentum Graecum, e codice Ms. Alexandrino, qui Londini in Bibliotheca Musei Britannici asservatur, descriptum a Carolo GodofredoWoide (Londini: ex prelo Joannis Nichols, typis Jacksonianis, 1786).(SPEC COLL BS1964.A5 1786 Oversize flat). The original manuscript is London, British Library, MS Royal 1.D.V-VIII.

For the first Christians, Aramaic and Greek were the common languages. Early Christians in Syria  used another dialect of Hebrew, called Syriac, and they translated the scriptures into this. In Egypt the Copts used their language, Ge' ez.

used another dialect of Hebrew, called Syriac, and they translated the scriptures into this. In Egypt the Copts used their language, Ge' ez.

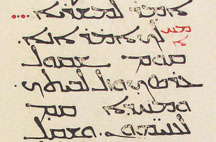

Shown at left is a page of the sixth-century Rabbula Gospels in Syriac. To the right is an enlarged detail of this elegant script. These are reproduced from: Rabbula Gospels. Facsimile Edition of the Miniatures of the Syriac Manuscript Plut. 1, 56 in the Medicaean-Laurentian Library. Edited with commentary by Carlo Cecchelli, Giuseppe Furlani, and Mario Salmi. Olten: Urs Graf, 1959. (SPEC COLL BS1992.5 R23 1959 OVERSIZE FLAT), Facsimile of fol. 159a.

COPTIC. Christians in Egypt translated the Bible into their language, Ge' ez, and illustrated their Gospel books with depictions that evoke their own culture. On display each month will be reproductions of two Coptic manuscript pages. The persons depicted are Copts. Likewise the birds adorning some margins are native to the region of the illustrator. Because the Coptic Church tended to be monophysite, believing that Jesus had one nature only, a divine one, they did not portray him as suffering on the Cross. Instead, they depicted a cross without the corpus of Jesus, but placed a lamb above the Cross to evoke the redemption symbolically. Because this cross is usually shown between the crosses with the two thieves, it is clear that it is the Crucifixion that is being represented.11

Most of the Eastern Church continued to use Greek. In the West, however, within a few centuries Latin-speaking Christians needed new double readings at liturgy, with the scripture read first in Greek and then translated into Latin. The Bible was soon translated into the common language of the people, Latin. But again, within a few centuries the vernacular languages of Europe developed. Biblical texts were swiftly put into these languages. The first written Italian literature is the translation of one of the psalms by St. Francis of Assisi, for instance, while a shepherd in England who worked for monks sang the Creation story in Old English verse to the accompaniment of his native harp. While Latin remained the liturgical language all Roman-Rite Catholics, the various vernaculars of Europe were used in homilies and catechesis and in manuscripts for devotional reading.

In Anglo-Saxon England, the people spoke Old English, and manuscripts survive with translations of major parts of the Bible, such as the Heptateuch (the first seven books of the Bible) and the Psalms. Manuscripts of homilies record the valuable evidence that priests would begin their homilies by translating the Latin Gospel into Old English so that the people would be sure to understand.

The Old English version of the Heptateuch, Aelfric' s Treatise on the Old and New Testament and His Preface to Genesis, ed. S. J. Crawford with N. R. Ker (Oxford University Press for the Early English Text Society, 1992, reprint 2004). On loan from Dr. Catherine Brown Tkacz. Gonzaga University owns this volume on microcard: PR1119.E5 no. 160. October: title page and frontispiece from British Library, MS Cotton Claudius B. IV, fol. 38r, with illustrations showing the Sacrifice of Isaac, a prefiguration of Christ' s sacrifice on the Cross. November: pp. 80-81, the beginning of Genesis. December: pp. 218-19, Exodus 3:14f, with God' s self-revelation to Moses.

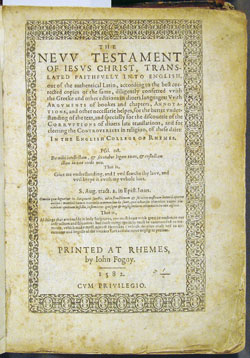

Douai-Rheims BibleThe University is privileged to own, as part of its valuable Gonzaga Collection, a full first edition of the Douai-Rheims Bible, the first complete Catholic Bible in English. Shown here is the title page of the New Testament (1588). Written in the time of Shakespeare, the Old Testament appeared in 1609-1610, a year before the first edition of the King James Version. To view more pages from this Bible, go to the online exhibition Treasures from the Vault and navigate down to Douai Rheims. The New Testament of Jesus Christ, translated faithfully into English, out of the authentical Latin, according to the best corrected copies of the same, diligently conferred with the Greeke and other editions in divers languages, with Arguments of bookes and chapters, Annotations, and other necessarie helpes, for the better understanding of the text, and specially for the discoverie of the Corruptions of divers late translations, and for cleering the Controversies in religion, of these daies. Printed at Rhemes: by John Fogny, 1582 (SPEC COLL BS180.1582). October: Front cover. November: Hebrews 12:1 ("Cloud of witnesses"). December: pp. 138-139 with Luke' s nativity account. The Holie Bible faithfully translated into English, out of the authentical Latin: Diligently conferred with the Hebrew, Greeke, and other editions in divers languages. With Arguments of the bookes, and chapters, annotations, tables, and other helpes, for better understanding of the text, for discoverie of corruptions in some late translations, and for clearing controversies in religion / By the English College of Doway ... 2 vols. Doway [Douai, France}: Printed ... by Laurence Kellam, at the signe of the holy lamb, 1609-1610. (SPEC COLL BS180.1609). Volume 1, October: title page. November: pp. 160-61, Exodus 3:14ff. December: Front cover. Volume 2, October: pp. 234-35, the Introduction to the Gradual Psalms, Ps. CXIX. November: front cover. December: Isaiah 7:14, the prophecy of the virgin birth. |

|

Dr. Catherine Brown Tkacz

Guest Curator

September 30, 2008

1. Pope Benedict XVI, "Encountering God in Catholic Education," address at The Catholic University of America, April 17, 2008, second paragraph.

2. Jesuit Oregon Province Archives, Joseph Cataldo, S.J., Personal Papers 6:11, where the slip of paper is inserted in one of several memo books in which he wrote his sermon notes.

3. Sacred Heart holy card: Jesuit Oregon Province Archives, Joseph Cataldo, S.J., Personal Papers 1:5. Slips of paper with "All good things," psalm notes, etc.: Jesuit Oregon Province Archives, Joseph Cataldo, S.J., Personal papers 5:17. Biblical passages he is working out in Nez Perce on these slips include Psalms 17:11, 23:7, 46:6-7, 83:1, 131:8, and 107:6 and Apocalypse 4:8, 48:5-12.

4. Lists of Montana Indian Languages and of locations where "Flathead is spoken," handwritten on both sides of an envelope: Jesuit Oregon Province Archives, Joseph Cataldo, S.J., Personal papers 6:19. Notes explaining Nez Perce toponyms (place names) on a memo sheet from the Schwab Printing Co: Jesuit Oregon Province Archives, Joseph Cataldo, S.J., Personal Papers 6:12

5. "Veni Creator": pp. 38-39). Other hymns in that volume include "Mary," "Confidence" and "Long Live the Pope": pp. 44, 45, 48.

6. Canons and Decrees of the Council of Trent: Original Text with English Translation, trans. H. J. Schroeder (London: B. Herder Book Company, 1941), p. 148.)

7. Hernando de Talavera, who became archbishop of Granada in 1496, promoted Arabic languages studies and the publication of linguistic and catechetical works for the clergy. Source: Alan Durston, Pastoral Quechua: The History of Christian Translation in Colonial Peru, 1550-1650. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2007. Citing Marcel Bataillon, Erasmo Espana, estudios sobre la historia espirituel del siglo XVI, translated by Antonio Alatorre, 2 vols. (Mexico City: Fondo del Cultura Economica,1950 [1937]), 1:68-69) and Albert G. Hauf i Valls, Fray Hernando de Talavera, O.S.H., y los traducciones castellanas de la Vita Christi de Fra Francesc Eiximenis, O.F.M., in Essays on Medieval Translation in the Iberian Peninsula, ed.Tomas Martinez Romero and Roxana Recio(Castello: Publicacions de la Universitat Jaume I, 2001): pp. 203-250, at pp. 232-236; and Bernardo Illari, Polychoral Culture: Cathedral Music in La Plata (Bolivia, 1680-1730); (University of Chicago, unpublished dissertation, 2001), p.152. Durston is more interested in language as a tool of colonization than a means of evangelization.

8. Durston, pp.1-2, 118, 222, cf. 35. For examples of Rojo Mejia y Ocon' s 1648 translations from the Gospel of John, see pl. 231. For the Third Lima Council (1585), see pp. 88-89, with Council text on p. 329.

9. papal quotations: P. Allard, "Christianity and Slavery," Catholic Encyclopedia, s.v.

10. Hebrew technical terms such as "Sadducee" and "Pharisee" were likewise retained from the New Testament. One can see an instance of Fr. Cataldo's keeping these terms in Nez Perce in Jesus-Christ-nim (on display in the first case), pp. 225-226, the opening exhibited in November.

11. On display at Cowles: Ewa Balicka-Witakowska, La crucifixion sans crucifie dans l' art ethiopien: Recherches sur la survie de l' iconographie chretienne de l''antiquite tardive, Biblica Nubica et Aethiopica, 4 (Warsaw and Wiesbaden: Zacutes Pan, 1997). (SPEC COLL ND3338.B36 1997). October: color plates III-IV, Gospel Book, Bibliotheque Nationale de France, eth. 32, fol. 7v, and Gospel Book of D'abra Ma'ar, fol.? November: col. pl. IX-X: Gospel Book of Zir Ganela (New York, Pierpont Morgan Library, M 828), fol. 14r, and Gospel Book of Maryam Magdalawit, fol.? December: col. pl. XI-XII, Gospel Book of Arsima Same'tat, fol. ?, and Gospel Book of Dabra Tensa'e, fol. ?