The presence of women in the iconography, texts, and liturgical calendar of the Dominican Missal of 1521 reflects a richly positive, ancient tradition. Already the digitized sample from that missal allows demonstration of how several women are positively depicted in that book and how women are throughout treated with respect. The complete digitizing of the volume will enable complete analysis of this important subject.

The tradition. Christianity, starting with the teachings and actions of Jesus himself, highlighted the spiritual equality of the sexes. The original revelation of Genesis had innovatively identified women as created equally in the image of God, and the Old Testament holds many accounts of women who were notable in their faith, courage, intelligence, successful prayers, and leadership.(1) Jesus emphasized the spiritual equality of the sexes by using pairs of parables featuring a woman and a man – such as the good shepherd and the good homemaker – and by interacting with women in ways that showed they were just as capable as men of understanding and professing the faith, seeking and receiving healing, interceding for others, etc.(2) This bore fruit at once in the equal access of both sexes to the sacraments of life – baptism and the Eucharist.(3) Although in the Temple in Jerusalem, women had been further from the sanctuary than the men, in Christian churches women “were included in the liturgy as a whole in exactly the same way as men” and were as close to the sanctuary.(4)

Also, starting in the first century, Christians began a pastoral program of the balanced representation of the sexes. This is widely evident in both texts and art.(5) St. James offered a sexually balanced pair of exemplars of faith, Abraham and Rahab (James 2:20-26), Clement of Alexandria (d. 215) preached a sermon affirming that “Women are Equally Capable with Men of Obtaining Perfection,” and St. John Chrysostom taught in a sermon that “You see everywhere vice and virtue, not differentiated by nature [i.e., sex], but by character.”(6) In the visual arts, frequently both a man and a woman are depicted in parallel ways. Both Adam and Eve are depicted at The Fall.(7) On a fourth-century ivory reliquary, a characteristic balance is seen, with both a man and a woman receiving healing, both a man and a woman being raised from the dead, and both a man and a woman dying because of sin.(8) A subject found several times in Early Christian art is the resurrection after death at a moment of personal judgment, and usually both a man and a woman are shown entering Heaven.(9) In churches, quite often both men and women are depicted adjacent to the sanctuary.(10) The Church calendar annually recalls both men and women important in salvation history, such as the Magi and the Women at the Tomb, and likewise commemorates both male and female saints.

Women in the Dominican Missal of 1521

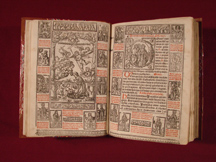

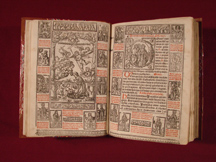

This rich heritage of the balanced representation of the sexes is seen in the Dominican Missal of 1521. Depictions of women include several pictures of Mary, the Mother of God, as well as other holy women. Importantly, a woman is included in the liturgical woodcut for Ash Wednesday. Often an opening – the two pages visible when the book is opened – includes a balance of the sexes in its illustration. The subject of the balanced representation of the sexes is timely and deserves further exploration, and the Dominican Missal of 1521 offers a valuable means of advancing such research. The rest of this webpage surveys all the ways in which women are depicted in the digitized sample from this Missal, and then offers suggestions for projects to examine the topic further.

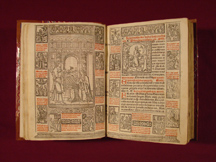

St. Catherine of Siena on titlepage? A woman is one of the four Dominicans surrounding St. Dominic on the titlepage. She is the figure at the far right. Given the holiness and cultural importance of St. Catherine of Siena, Doctor of the Church, it is likely that she is the specific woman depicted.

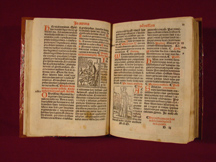

St. Anastasia. Only two saints who are not apostles or evangelists are represented in portrait-woodcuts in the portion of this missal digitized to date: St. Anastasia (fol. 11) and St. Lawrence (fol. 22). St. Anastasia, whose name means “Resurrection,” was martyred on Christmas day; she is depicted in a portrait-woodcut beside a prayer invoking her. Her name, in red ink, is just above the prayer. In Rome this feast was celebrated by the pope at the church commemorating her.(11) St. Lawrence, too, had a church in Rome which was the “stational church” for a particular liturgical occasion when the pope would celebrate the liturgy there: St. Lawrence’s day was the Third Sunday before Ash Wednesday. Thus in these two saints is seen again the balance of the sexes in the Church calendar, in this case, in the designation of stational churches.

St. Anastasia. Only two saints who are not apostles or evangelists are represented in portrait-woodcuts in the portion of this missal digitized to date: St. Anastasia (fol. 11) and St. Lawrence (fol. 22). St. Anastasia, whose name means “Resurrection,” was martyred on Christmas day; she is depicted in a portrait-woodcut beside a prayer invoking her. Her name, in red ink, is just above the prayer. In Rome this feast was celebrated by the pope at the church commemorating her.(11) St. Lawrence, too, had a church in Rome which was the “stational church” for a particular liturgical occasion when the pope would celebrate the liturgy there: St. Lawrence’s day was the Third Sunday before Ash Wednesday. Thus in these two saints is seen again the balance of the sexes in the Church calendar, in this case, in the designation of stational churches.

Mary, the Mother of God. For her importance in the Incarnation, Mary is often depicted. She is seen in the large miniatures adorning major feasts: Christmas Eve (fol. 7v, shown immediately below), the Adoration of the Shepherds (fol. 11v, shown at left), the Presentation (fol. 14v), and the Adoration of the Magi (fol. 16v). On some of the openings for major feasts she is shown a second time in the historiated initial on the righthand page (fols. 12 [shown at left], 15, 17). There is also a decorated opening for the feast of the Purification of Mary (fols. 171v-172), with the same large woodcut used for the Presentation (fol. 14v) and a new historiated initial S (fol. 172) that depicts the churching of Mary. She holds a large lighted candle before the open door of the church; a vested priest extends his cross-adorned stole to her and she holds it, about to be led by him into the church.

In woodcuts illustrating Gospel lections Mary is also essential. Thus she is shown with Joseph going to Bethlehem (fol. 8v, also in the upper right of fol. 7v), holding her infant son as the Magi worship him (fol. 17v), with Joseph finding the boy Jesus in the Temple (fol. 18), and in a striking depiction of the Wedding at Cana, a composition which uses a strong diagonal (fol. 19v).

The headpieces. Every fully decorated opening has two headpieces, one atop the lefthand page and one atop the right. Mary is featured in two of the three headpieces which recur in the highly decorated openings for major feasts. One headpiece depicts Christ, in a cruciform halo, prominently in the center, with six haloed disciples on either side of him, looking toward him. A second headpiece is clearly designed as a companion to this, for it depicts Mary, haloed, prominently in the center, with five haloed holy women on either side of her, looking toward her. On the opening for Christmas eve (fols. 7v-8, shown at right) this headpiece with Mary is on the first page and the headpiece with Christ is on the second. As a result the opening shows a balance of the sexes, with holy women atop one page and holy men atop the other.

The third headpiece shows the coronation of the Blessed Virgin Mary (fols. 10, 12, 63v). The other two headpieces simply present all figures from the shoulders up, in order to fit the restrictions of the short, wide shape of the headpiece atop a page. In the third headpiece, however, the designer managed to fit three-quarter-length figures into a complex scene involving a coronation and a full orchestra. As seen in the image to the left, atop the righthand page (fol. 10), Mary sits centrally, the only lowly placed figure: She is on a throne, but it is placed below the level of the other figures in the headpiece. The Trinity are prominent, not Mary: Christ is at her left, God the Father to her right, and above her the Holy Spirit descends in the form of a dove, with all three persons of the Trinity holding the crown and lowering it upon her head. At the same time, Mary is the only frontal figure, and she is central, so she is focal. Her hands are palm to palm before her in reverence. On the ends of the headpiece are an angelic four-piece orchestra with angels playing a stringed instrument with a bow, a lute, an organ, and a flute, while three cherubs perhaps serve as singers. This headpiece is often paired with the headpiece of Christ amid the disciples (fols. 9v, 11v, 64), so again the balance of the sexes is given on these openings.

The third headpiece shows the coronation of the Blessed Virgin Mary (fols. 10, 12, 63v). The other two headpieces simply present all figures from the shoulders up, in order to fit the restrictions of the short, wide shape of the headpiece atop a page. In the third headpiece, however, the designer managed to fit three-quarter-length figures into a complex scene involving a coronation and a full orchestra. As seen in the image to the left, atop the righthand page (fol. 10), Mary sits centrally, the only lowly placed figure: She is on a throne, but it is placed below the level of the other figures in the headpiece. The Trinity are prominent, not Mary: Christ is at her left, God the Father to her right, and above her the Holy Spirit descends in the form of a dove, with all three persons of the Trinity holding the crown and lowering it upon her head. At the same time, Mary is the only frontal figure, and she is central, so she is focal. Her hands are palm to palm before her in reverence. On the ends of the headpiece are an angelic four-piece orchestra with angels playing a stringed instrument with a bow, a lute, an organ, and a flute, while three cherubs perhaps serve as singers. This headpiece is often paired with the headpiece of Christ amid the disciples (fols. 9v, 11v, 64), so again the balance of the sexes is given on these openings.

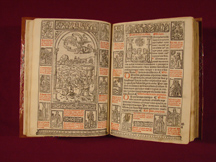

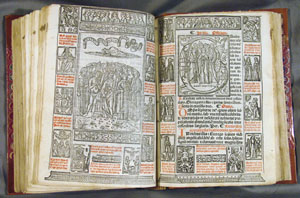

Balanced representation of the sexes. Pairing a Marian headpiece with the one depicting Christ visually sets forth balanced representation of the sexes on the openings for four major feasts (fols. 7v-8, 9v-10, 11v-12, 16v-17). Mary’s presence in many depictions from the history of the nativity and infancy of Christ results in female depiction beside him in several contexts. Shown at right is the opening for the Feast of Epiphany (fols. 16v-17). On these two pages Mary is depicted five times: in the two largest woodcuts, in which she holds the infant Lord while the Magi adore Him; in the headpiece of holy women on the lefthand page, and in two marginal woodcuts on that page (upper left and third down on the right).

Balanced representation of the sexes. Pairing a Marian headpiece with the one depicting Christ visually sets forth balanced representation of the sexes on the openings for four major feasts (fols. 7v-8, 9v-10, 11v-12, 16v-17). Mary’s presence in many depictions from the history of the nativity and infancy of Christ results in female depiction beside him in several contexts. Shown at right is the opening for the Feast of Epiphany (fols. 16v-17). On these two pages Mary is depicted five times: in the two largest woodcuts, in which she holds the infant Lord while the Magi adore Him; in the headpiece of holy women on the lefthand page, and in two marginal woodcuts on that page (upper left and third down on the right).

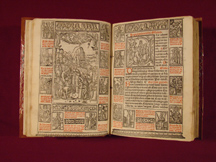

Notably, the balance of the sexes is highlighted in the woodcut representing the Presentation of Christ in the Temple (fols. 14v-15). Two depictions on the opening at the head of this feast show an equal number of men and women. Often artworks showing this event show four persons with the infant Jesus: Mary and Joseph, and the elderly Symeon and Anna (Luke 2:21-40).(12) Here the aged widow Anna is depicted kneeling in homage to the holy infant, the artist’s way of showing that this prophetess recognized that the baby was the Lord incarnate (Luke 2:36-38).

Notably, the balance of the sexes is highlighted in the woodcut representing the Presentation of Christ in the Temple (fols. 14v-15). Two depictions on the opening at the head of this feast show an equal number of men and women. Often artworks showing this event show four persons with the infant Jesus: Mary and Joseph, and the elderly Symeon and Anna (Luke 2:21-40).(12) Here the aged widow Anna is depicted kneeling in homage to the holy infant, the artist’s way of showing that this prophetess recognized that the baby was the Lord incarnate (Luke 2:36-38).

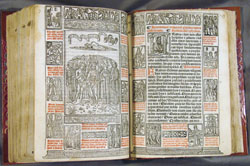

Ash Wednesday liturgical woodcut. One of the two liturgical vignettes for Ash Wednesday shows a vested priest distributing ashes (fol. 26). Significantly, both a man and a woman are shown with him, the man in the act of receiving the ashes and the woman waiting reverently to receive. Thus the artist models the appropriate posture for receiving and for approaching to receive. At the same time, both male and female are shown in this important liturgical action.

Ash Wednesday liturgical woodcut. One of the two liturgical vignettes for Ash Wednesday shows a vested priest distributing ashes (fol. 26). Significantly, both a man and a woman are shown with him, the man in the act of receiving the ashes and the woman waiting reverently to receive. Thus the artist models the appropriate posture for receiving and for approaching to receive. At the same time, both male and female are shown in this important liturgical action.

Unidentified depictions of women. Depictions of women are among the many small woodcuts that edge the decorated openings that start major feasts. For instance, Christ is shown at table with two women in the second woodcut from the left on the bottom of folio 1. The opening for Christmas Eve has several female figures in the small woodcuts, including a small nativity scene at the far left. This category of woodcuts in the Dominican Missal has not been studied yet, and few of their subjects have even been identified. As a result their representation of women is yet to be researched.

Unidentified depictions of women. Depictions of women are among the many small woodcuts that edge the decorated openings that start major feasts. For instance, Christ is shown at table with two women in the second woodcut from the left on the bottom of folio 1. The opening for Christmas Eve has several female figures in the small woodcuts, including a small nativity scene at the far left. This category of woodcuts in the Dominican Missal has not been studied yet, and few of their subjects have even been identified. As a result their representation of women is yet to be researched.

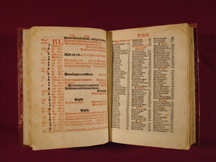

Calendar of Saints. Even though the portion of the Dominican Missal of 1521 containing the commemorations of individual saints has not yet been digitized, the table of contents for it has. Once the rest of the missal has been digitized, it will be easy to explore it for depictions of female saints listed in the table of contents, including Sts. Prisca, Agnes, Agatha, Dorothy, Apollonia, Scholastica, Petronilla, Margaret, Mary Magdalene, Christina, Anne, Martha, Cecilia, Barbara, Lucy, Euphemia. Also, there may well be woodcuts with other Marian feasts, such as her nativity (fol. 221), her presentation (278), and her Assumption (216).

Calendar of Saints. Even though the portion of the Dominican Missal of 1521 containing the commemorations of individual saints has not yet been digitized, the table of contents for it has. Once the rest of the missal has been digitized, it will be easy to explore it for depictions of female saints listed in the table of contents, including Sts. Prisca, Agnes, Agatha, Dorothy, Apollonia, Scholastica, Petronilla, Margaret, Mary Magdalene, Christina, Anne, Martha, Cecilia, Barbara, Lucy, Euphemia. Also, there may well be woodcuts with other Marian feasts, such as her nativity (fol. 221), her presentation (278), and her Assumption (216).

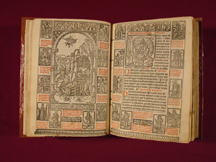

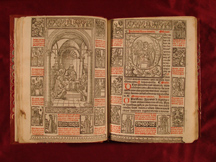

All Saints. Exciting evidence is found in this missal, evidence emphasizes the spiritual equality of the sexes. The inscription in a woodcut shows that the grammatical masculine generic was experienced generically. That is, people recognized themselves as fundamentally human, sharing a common humanity regardless of their sex. A single woodcut is used for All Saints Day (fols. 232v-233, shown at right) and again for the Feast of One or More Apostles (fols. 238v-239, shown immediately below).(13) It shows a group of men and women on a hillside representing Paradise. The group includes twelve distinct individuals, with more indicated behind them. Among the twelve are perhaps St. Jerome (second from the left); a pope and a bishop, recognizable by their regalia; St. Peter in the front; and at the right two or more women.(14) In the sky above them is a scroll with the words that God the Father spoke from Heaven at the Baptism of Christ, but here the words are made plural: Hii sunt mei filii dilecti, “These are my beloved sons.” The same design and inscription as in this woodcut (and thus perhaps the very same woodcut) are found in the miniature used with the Office for All Saints Day in a small breviary of the late fifteenth or early sixteenth century, which suggests that that breviary may also have been printed by Giunta, the publisher of the Dominican Missal of 1521.(15)

All Saints. Exciting evidence is found in this missal, evidence emphasizes the spiritual equality of the sexes. The inscription in a woodcut shows that the grammatical masculine generic was experienced generically. That is, people recognized themselves as fundamentally human, sharing a common humanity regardless of their sex. A single woodcut is used for All Saints Day (fols. 232v-233, shown at right) and again for the Feast of One or More Apostles (fols. 238v-239, shown immediately below).(13) It shows a group of men and women on a hillside representing Paradise. The group includes twelve distinct individuals, with more indicated behind them. Among the twelve are perhaps St. Jerome (second from the left); a pope and a bishop, recognizable by their regalia; St. Peter in the front; and at the right two or more women.(14) In the sky above them is a scroll with the words that God the Father spoke from Heaven at the Baptism of Christ, but here the words are made plural: Hii sunt mei filii dilecti, “These are my beloved sons.” The same design and inscription as in this woodcut (and thus perhaps the very same woodcut) are found in the miniature used with the Office for All Saints Day in a small breviary of the late fifteenth or early sixteenth century, which suggests that that breviary may also have been printed by Giunta, the publisher of the Dominican Missal of 1521.(15)

The implications of this image are culturally significant. The fact that women as well as men are depicted in this woodcut indicates that “sons” is intended generically, to include both male and female. That these words are used here indicates that the saints being commemorated, both men and women, have become Christlike. More widely, this indicates that everyone is called to become Christlike and is created capable of doing so. Christian anthropology is the understanding of what human nature is, Fundamental to Christian anthropology is the belief that the vocation to holiness is universal, common to every man, woman and child. This message is reinforced by the headpieces used on the opening for the celebration of “One or More Apostles” (shown at left). On this opening the headpiece of the coronation of the Blessed Virgin Mary tops not just one, but both pages. Here Mary is shown as human model for heavenly life. She is also a powerful reminder that women are, equally with men, created with the full capacity for holiness.

The implications of this image are culturally significant. The fact that women as well as men are depicted in this woodcut indicates that “sons” is intended generically, to include both male and female. That these words are used here indicates that the saints being commemorated, both men and women, have become Christlike. More widely, this indicates that everyone is called to become Christlike and is created capable of doing so. Christian anthropology is the understanding of what human nature is, Fundamental to Christian anthropology is the belief that the vocation to holiness is universal, common to every man, woman and child. This message is reinforced by the headpieces used on the opening for the celebration of “One or More Apostles” (shown at left). On this opening the headpiece of the coronation of the Blessed Virgin Mary tops not just one, but both pages. Here Mary is shown as human model for heavenly life. She is also a powerful reminder that women are, equally with men, created with the full capacity for holiness.

|

Use of this woodcut for commemoration of one or more apostles deserves comment. The Church acknowledges men and women with major evangelical achievements as apostles or “equal to the apostles” (Greek: isapostolos). St. Jerome described the women at the tomb on Easter morning as “apostles of the apostles” because these women conveyed the good news of the resurrection of the Lord to the disciples. (16) Thomas Aquinas and other doctors of the Church also praise Mary Magdalene’s “apostolic office.” Other female saints hold the title of isapostolos in the Byzantine Catholic Church and the Orthodox Church.(17) The Dominican Missal of 1521 was printed in Italy, where Byzantine influence was sometimes strong. The use of this woodcut for apostles may reflect such influence and the conscious recognition of certain holy women as “equal to the apostles.” |

Projects

1. Is it possible to identify definitely the woman on the titlepage of the Dominican Missal of 1521? Is it certain that this is St. Catherine of Siena? How might this be determined?

2. In the headpiece in which ten women surround Mary (fol. 7v and fol. 16v) is the number ten significant? In the Parable of the Ten Virgins, only five were wise, while five were foolish (Matt. 15:1-13), so it seems unlikely that this parable is the referent.

3. Is it possible to identify all seven individual figures in the main miniature of the Presentation in the Temple (fol. 14v)?

4. Is it possible to identify the individual figures in the historiated initial depicting the Presentation in the Temple (fol. 15)?

5. Analyze as fully as possible the woodcut used with the feast of All Saints and the celebration of One of More Apostles. Clearly the differing hairstyles and garments indicate in general the diversity of persons who are saints. Is anything more specific intended? How might that be determined?

6. Identify small woodcuts depicting women in the openings for major feasts. In each case, determine which red caption explains the specific woodcut and then use the caption’s information to help identify the woman. In some cases these woodcuts represent historical women, such as Mary, and in other instances they may represent allegorical figures.

7. Using scholarship on the Giunta publishing family, seek information on the representation of musical instruments in woodcuts they used.(18) With that, try to identify more precisely the instruments played by the angelic choir in the woodcut showing the coronation of Mary.